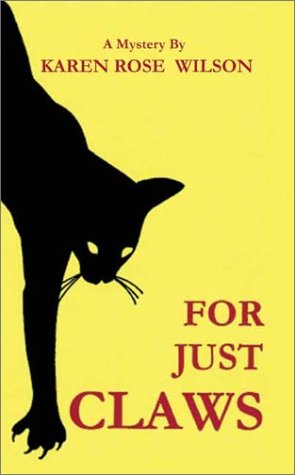

For Just Claws by Karen Rose Wilson

Order an autographed copy from the author

Order at a Store

Format:

Paperback, 164pp. Format:

Paperback, 164pp.ISBN: 0759680671 Publisher: 1stBooks Library Pub. Date: March 2002 |

PROLOGUE

Our small town of Hadley, nestled in the rolling green hills of lower Michigan, is normally pretty quiet. We ride our horses, pay our bills and sometimes forget to lock our doors. Murder and mercy killing, robbery and street protests are distant evils, things we read about in the Sunday newspaper, published forty miles away in Detroit, and brought by truck in the middle of the night.

All that was about to change.

CHAPTER

ONE

I swung my lead rope and clucked to the two chestnuts eyeing me suspiciously from the corner of the paddock. I worked them, sending them swerving and turning, controlling their movements, outside turn, inside turn, herding them into the barn. Their hooves flung clods of black April muck, as they trotted to their stalls and I threw home latches behind them. The phone in the tack room sent me racing, counting the rings before the answering machine in the house picked up.

“What time are we saddling up?”

Puffing from the run, I glanced at my watch. “Hi Denise. I just brought the horses in. Feather’s a real pigsty, mud from stem to stern.” I fiddled with a balled-up spider carcass lying on the window ledge, rolling it between my fingers. “Grooming her isn’t going to be quick. Let’s meet in the meadow, at, say, half past twelve?”

“Great. I can’t go for a long ride, got to be home by two. Todd and I are leaving for the hospital at three.”

“How’s his mom doing?” I asked, dropping the spider into the trash can.

“The cancer is taking over, day by day. Nothing will stop it now. We feel so helpless.”

“How’s Todd taking it?”

“We have these awful silences, when I ask him about things, like her will or her funeral, and he answers in a single word, then he doesn’t want to talk anymore.”

“Give him time, he’ll come around.”

“Time is the one thing we don’t have. Somebody’s got to talk to her about the important stuff. Does she want to be cremated or buried? Life support or not? But no, they talk about trivial things, like the weather or who won the baseball game.”

“It hasn’t sunken in yet. What’s obvious to us, I mean. He’s still denying that she’s dying.”

“He knows the truth, just as sure as you and I.”

Feather fidgeted on the cross-ties, shifted her weight, and cocked her right hind heel. “Not to change the subject, but I’ve got housecleaning and grocery shopping on today’s agenda, so I can’t go for a long ride either.”

“Sounds good. See ya’ later.”

I curried and brushed my mare, picked out her feet and combed her mane and tail. Stretchy neoprene wraps went on to protect her legs and support old, worn tendons.

Her stablemate, Echo, poked his head over his Dutch door and yawned. “Tomorrow’s your turn,” I reminded him. “Feather goes today and you go tomorrow.” He shook his head, flapping his tongue against the stall door.

Closing the paddock gate behind us, I led Feather across the lawn and stood on the picnic table, positioning the mare alongside, to slide my foot into the stirrup. We ambled down the gravel road, sun peeking through cottony clouds and a warm breeze ruffling last autumn’s damp leaves. The dirty snow had melted, giving way to spring flowers crowning moist earth.

I tapped my heels against Feather’s sides and we trotted onto a path that wound around some honeysuckle bushes and opened into a meadow. Following a narrow deer trail through the meadow, this was a shortcut that saved riding up a steep, rocky hill on the gravel road. Lemon-yellow sulphurs flitted among the yet unfurled honeysuckle buds.

Feather’s ears twitched forward and back, listening. We scrambled over the rubble of an old stone wall and stepped onto a two-track left by hunters, rutted with the deep gouges of four-wheel drives. A hundred feet to the south, the two-track dead-ended into the county road.

Denise and I usually met along this stretch, where the land is state owned and posted as equestrian trails and, during hunting season, open to hunters. I closed my legs around Feather’s sides, almost imperceptibly released the reins, and we broke into a canter, her steel horseshoes rhythmically clicking on the stony path. Rounding a curve, Denise rode toward us.

She pulled up her gelding, Beezer, and turned him, so he and Feather walked side by side. “Like your hair,” I said. She’d gotten it done since I last saw her. “Nice highlights.” Her brown eyes, fringed in dark downcast lashes, gave her a coy princess charm.

“I stopped by Jill’s salon Thursday after work,” she said. “She did my hair while I looked at pictures of her new filly.” She pulled a pack of cigarettes from her denim jacket and lit one. The smoke curled and spiraled upward, like spirits rising to heaven.

“Having a sister that’s a hair stylist definitely has its perks. What’s the new horse like?” I asked.

“It’s not a yearling, like she wanted. She ended up getting a two-year-old through one of her trainers.”

“A two-year-old is better anyway. She won’t have to pour as much time and money into her before she’s rideable.”

“The down side is that she had to pay more than she expected.”

“Looks like she’ll need a few more of those hundred-dollars-a-cut customers to help pay the bills.” We were at a fork in the two-track. “Which way?” I asked.

“Let’s take Blood Road, go through the pines and up the big hill to the overlook.” She pulled an old prescription bottle from her pocket, pinched the end of her cigarette butt, and dropped it into the bottle. “How’d they ever come up with a name like Blood Road?” she asked.

“You never heard the rumor? Way back when we were in high school?”

She shook her head. “I wasn’t raised around here, remember? I was a city girl.”

“Yeah, I always forget.” She seemed so at ease in the country, with her horses and dogs and chickens, I always forgot she was transplanted. “Well, the story was that couples came out here to park or party, drink beer, whatever. With it being so desolate, no houses and all, it was a popular spot. Supposedly a couple stopped to park but left their radio playing. When they wanted to go home, the battery was drained and the car wouldn’t start, so he said he would walk to the nearest house for help. He told her to lock all the doors and not to let anybody in, except him. Sometime in the night, she fell asleep, but dreamed she heard a tapping noise.”

“And no doubt it was a stormy, moonless night,” Denise said skeptically.

“Of course,” I said. “When the sun came up, she found the source of the tapping—her boyfriend hung from a tree, a noose around his neck, his shoes tapping the driver’s side window.”

She threw me a crooked grin and tucked a lock of hair behind her ear. “You believe that?” she asked.

“Of course not,” I laughed. “But that’s why it’s called Blood Road.” The road was sandy and straight here, perfect for a short gallop. “Let’s canter,” I called to her.

Feather surged forward when I drew back my leg and laid my heel against her side. The wind whistled past. At Blood Road, we slowed to a walk and turned right, then took a path leading to a stand of towering Tamarack pines so dense and dark and foreboding that even on the brightest day, only a blue-green streak of light passed through to the forest floor. Silent except for the crunch of hooves on fallen pine needles and creaking saddle leather, the pine forest was a mystical vacuum cut off from the rest of the world.

We went up a steep hill, where erosion exposed the gnarled roots of the tall pines. The horses carefully picked their way over the roots, some as thick and strong as woven nylon rope. At the top of the hill, out of the shadows of the Tamaracks, welcome sunlight streamed down again. The horses puffed from the long climb.

“Oh, I almost forgot to tell you,” said Denise, “remember Kathy’s son, Derrick? He’s come back to live with her.”

“As if she doesn’t have enough to do--the only ranger managing a four-thousand acre state park--now she’s got him to look after, too.” Less than thrilled to hear he was in the neighborhood, I said, “Nail down everything that moves and board up your house.”

“Carol, give the kid a chance. He’s been gone three years.”

“In the first place, he’s not a kid. He must be seventeen by now. And in the second place, you know Kathy only sent him to live with his dad in Detroit because she couldn’t do a thing with him. And I hate to generalize, but Detroit hasn’t been voted best community to raise children in lately, so I doubt he’s improved.”

“She says he’s grown up a lot. Some of the bad things he did were just part of being a kid.”

“So being a kid gives free license to be a kleptomaniac?”

“Would you want to be judged the rest of your life on what you did as a teenager? Give him another chance, even if just for Kathy’s sake.”

“Let’s say I’m not ready to have him house-sit while Jack and I go on vacation.”

“Honestly, Carol, you’d be suspicious of Noah, if it was raining and he offered you a lift in his Ark.”

“I’m not that bad, I’m just realistic. I can’t help it; it comes from living with Jack.” Husbands are easily blamed for shortcomings. I figured he had it coming, since it was his cynical nature rubbing off on me.

After climbing the last ridge to the overlook, we let the horses snack on grass while Denise and I dangled our feet out of our stirrups. We could see far to the south, over the tops of the trees, and all the way to the water tower fifteen miles away.

“Guess I’d better head home,” Denise said. “Wish I could ride longer.”

“Me too. You know how weekends are--errands, laundry, housecleaning, grocery shopping. It’s always a mad rush to catch up, like fitting your entire life into two days a week.”

“The hectic life of a working woman,” she said. “Want to ride tomorrow if it doesn’t rain?”

“Sure. Around one o’clock?”

“It’ll be Echo’s turn.” I always reminded her when I brought Echo, my problem horse. Last fall, he grabbed Beezer’s bridle and pulled it off his head, breaking the bridle in the process. Denise rode home with a polo wrap fashioned into a makeshift headstall. Another time, he bit Beezer’s knee. A third time he took hold of Beezer’s tail and yanked it, starting a kicking spree that ended with Denise face down in the dust.

“We’ll just stay far enough apart so he can’t get into mischief,” she said.

“You’re so good natured about his naughtiness. I don’t think I’d be as charitable.”

“He’s just playful. And it’s not like he’s ever done any real damage. You’ve got to let them have their personalities, Carol, just like kids.”

“He’s got a personality, all right—a bad one. A thousand pounds of juvenile delinquent, with poor vision and the mentality of a scared rabbit.”

She laughed. “You’re too hard on him. It’s a good thing you never had kids. They wouldn’t have ever had any fun.”

“At least they wouldn’t be total brats, either, like most kids nowadays. They aren’t taught any respect, the way we were.”

“This is a discussion for another day, Carol Ward, you old fogey.” She smiled. “I’ve got to go.”

“Just cut me off, mid-sentence, that’s okay,” I complained. “No respect for your elders.” Denise was exactly six months younger than me.